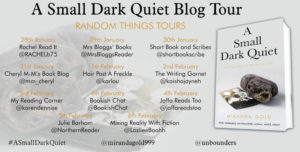

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #GuestPost by Miranda Gold, Author of A Small Dark Quiet @mirandagold999 #RandomThingsTours @Unbound_Digital

I’m very pleased to be posting today as part of the blog tour for A Small Dark Quiet by Miranda Gold. Miranda has very kindly written a fabulous guest post for me to share with you. My thanks to Anne Cater from Random Things Tours for the place on the tour.

![]()

March, 1945. The ravaged face of London will soon be painted with victory, but for Sylvie, the private battle for peace is just beginning. When one of her twins is stillborn, she is faced with a consuming grief for the child she never had a chance to hold. A Small Dark Quiet follows a mother as she struggles to find the courage to rebuild her life and care for an orphan whom she and her husband, Gerald, adopt two years later.

Born in a concentration camp, the orphan’s early years appear punctuated with frail speculations, opening up a haunting space that draws Sylvie to bring him into parallel with the child she lost. When she gives the orphan the stillborn child’s name, this unwittingly entangles him in a grief he will never be able to console. His own name has been erased, his origins blurred. Arthur’s preverbal trauma begins to merge with the loss he carries for Sylvie, released in nightmares and fragments of emerging memories to make his life that of a boy he never knew. He learns all about ‘that other little Arthur’, yearning both to become him and to free himself from his ghost. He can neither fit the shape of the life that has been lost nor grow into the one his adopted father has carved out for him.

As the novel unfolds over the next twenty years, Arthur becomes curious about his Jewish heritage, but fears what this might entail – drawn towards it, it seems he might find a sense of communion and acceptance, but the chorus of persecutory voices he has internalised becomes too overwhelming to bear. He is threatened as a child with being sent back where he belongs but no one can tell him where this is. He wanders as an adult looking for purpose but is unable to find his place. Feeling an imposter both at home and in the city, Arthur’s yearning for that sense of belonging echoes in our own time.

Meeting Lydia seems to offer Arthur the opportunity to recast himself, yet all too soon he is trapped in a repetition of what he was trying to escape. A past he can neither recall nor forget lives on within him even as he strives to forge a life for himself. Survival, though, insists Arthur keeps searching and as he opens himself to the world around him, there are flashes of just how resilient the human heart can be.

Through Sylvie’s unprocessed grief and Arthur’s acute sense of displacement, A Small Dark Quiet explores how the compulsion to fill the empty space death leaves behind ultimately makes the devastating void more acute. Yet however frail, the instinct for empathy and hope persists in this powerful story of loss, migration and the search for belonging.

![]()

Time in the Pysche, Time on the Clock by Miranda Gold

As part of The Random Things Blog tour, author Miranda Gold explores the instability of memory and its relationship to time, language, perception and the imagination, opening up questions that lie at the heart of her new novel, A Small Dark Quiet.

‘We had the experience but missed the meaning.’ Four Quartets, T.S Eliot

‘Memory is the seamstress, and a capricious one at that.’ Orlando, Virginia Woolf

How can we tell where memory ends and imagination begins when memory can only take place in the imagination? If the presence of the past is made palpable through our response – both in the sensations it produces and the way it recasts our perception of the world around us – it’s held most acutely in those unanticipated, external or physiological cues, variations on a theme of Proust’s madeleine, perhaps. The prompt itself may be fleeting but what sustains it is our own reconstruction, the details that becomes magnified as we recall, that we elaborate as we engage with it – or, as it can sometimes seem, insists on engaging us: it’s as much something we create as retrieve. Memory, this slippery mental construct, is threaded into our physical reality.

Each time we revisit a moment – or that moment revisits us via our senses – we can’t help but have a new encounter with a former self. But once the prompt sends or pulls us back and we slip through the open door, do we become a part of the scene or merely an observer? Or to put it another way, whose eyes are we looking through? It becomes dizzyingly meta if we try to separate the layers and impressions, especially when the imprint is activated through the body. As a reader suggested to me, the characters in A Small Dark Quiet don’t remember, they re-live: the past ruptures the present and former and present self seem to merge. This blurring becomes particularly disorientating when the memory can’t be located – if we can place and are able to secure it within a narrative structure, it can’t submerge us, we can demarcate the line that separates now from then, however tenuous that line might be. Without it the past can threaten to engulf – but here’s the paradox: self preservation seems to depend upon splitting off from oneself. This apparent contradiction is one I seem to keep coming back to and one I feel freer to explore through fiction, perhaps because translating it into language, which shares memory’s instability, mirrors the way it is reimagined by the reader whose context and associations rework the character’s experience. We often qualify our response to a novel as subjective, but it’s inter-subjective. Shift the angle, defamiliarise and it starts to come into focus: memory is both antagonist and guide.

In Greek mythology the river Mnemosyne runs parallel to the river Lethe in Hades, drinking from the former assures recollection, drinking from the latter promises oblivion – forgetting frees the souls from their previous incarnation. Mnemosyne is the name given to the goddess of memory, mother of the muses, she not only connects humanity to its history, she gives birth to the arts that will find a shape for that history. The tension between the need to split off from one’s past and the urge to recapture that past is at the centre of A Small Dark Quiet. The rhythm created through recurring images can be a way of suggesting a sense of the pattern this produces, one of continual flight and return. The image, though, like memory, isn’t quite a replica, it can’t be seen in quite the same light. However subtle, the shift can indicate that time in the psyche is trying to catch up with time on the clock. My sense is that the more extreme the disjunction between the two, the more the character becomes paralysed, caught between timeframes, between states, making them not only outsiders to the world but to themselves. They are both living on the periphery of their experience and consumed it. I wonder if it is at the point that memory becomes not just fantasy, but hallucination, displacing the present altogether. Imagery gives way to sensation, in fact the less concrete the scene, the more potent it seems to become – the stream of impressions can’t be tamed or related the way a clearly defined picture can – it escapes but is inescapable.

How then, to find a way to communicate the experience of what Eva Hoffman describes in her meditation on the aftermath of the Holocaust, After Such Knowledge, as ‘wrestling with shadows’? Eva’s book has become an anchor for me, capturing how memories are transmitted and become an ineradicable part of our being even as they take on the quality of myth. The power of these memories lies behind words and images and in the gaps between – it is precisely because they refuse representation that they hold this irreducible power. My sense is that if we are to attempt to communicate this there has to be space for the silence and the shadows within the writing, an admission of where language breaks down, where narrative is forced to break off and an acknowledgement, too, that ‘narrative is not always salvational.’

Thank you so much, Miranda, for such an interesting post.

![]()

![]()

Concert pianist in a parallel universe, novelist in this, Miranda Gold is a woman whose curiosity about the instinct in us all to find and tell stories qualifies her to do nothing but build worlds out of words.

Concert pianist in a parallel universe, novelist in this, Miranda Gold is a woman whose curiosity about the instinct in us all to find and tell stories qualifies her to do nothing but build worlds out of words.

Miranda’s first love was theatre and advises anyone after a dose of laughter in dark (along with a ferocious lesson in subtext) to look no further than the cheese sandwich in Pinter’s The Homecoming. No less inspiring were the boisterous five year olds she taught drama to and the youth groups she supported to workshop and stage their scripts. Both poetry and its twin, music, have been fundamental in her process as a writer and her hope is that the novel can tap into some of their magic to unleash the immediacy and visceral power of language – qualities that keep the reader on the page as well as turning it. Gatsby, To the Lighthouse and The Ballad of the Sad Café are books she will always come back to, always finding another door left ajar. Having the opportunity to mentor prisoners at Pentonville reaffirmed for her the connections that can be made when we find a narrative and a shape that can hold experience. There have been fleeting fantasies of becoming a Flamenco dancer, but sadly she has the coordination of an inebriated jelly fish.

Her first novel, Starlings, published by Karnac (2016) reaches back through three generations to explore how the impact of untold stories ricochets down the years. In her review for The Tablet, Sue Gaisford described Starlings as “a strange, sad, original and rather brilliant first novel, illumined with flashes of glorious writing and profound insight, particularly into the ways in which we attempt to reinvent ourselves.” Before turning her focus to fiction, Miranda attended the Soho Course for young writers where her play, Lucky Deck, was selected for development and performance.

Discover more from Short Book and Scribes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for the Blog Tour support Nicola