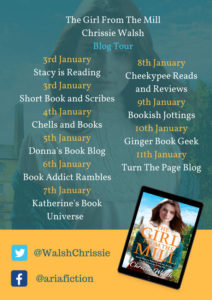

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Extract from The Girl From the Mill by Chrissie Walsh @WalshChrissie @aria_fiction

I’m so pleased to be taking part in the blog tour for The Girl From the Mill by Chrissie Walsh today and I have a lovely extract to share with you. My thanks to Vicky Joss from Aria for the place on the tour.

![]()

As World War I begins, life will never be the same again. A heart-breaking saga for all fans of Dilly Court and Val Wood.

In the drab Yorkshire town of Garsthwaite, Lacey Barraclough works hard in the textile mill, determined to fight for improvements to the dismal working conditions she and her fellow weavers face. But she hadn’t reckoned on falling in love with the boss’s son, Nathan. Nathan returns her love, but to succeed they must overcome the class divide, as well as persuade their families that their love for each other is real.

Before Nathan and Lacey can make a life together, World War I breaks out and Nathan enlists to fight. When Nathan heads off to the Front, he takes Lacey’s dreams with him, and she must find a new way to face the future. As hard times come to Garsthwaite, will there be a home for the returning heroes to come back to? And for those men who do make it back from France, can they ever outrun the horrors they have witnessed, and learn to love again?

Buy links

![]()

Long before Lacey Barraclough reached the outskirts of Garsthwaite, a dirty little mill town in the Colne Valley, her armpits and the hand that held her basket were already sticky with perspiration. It was shortly before six o’ clock on a bright June morning, and the sun’s strengthening rays signalled that today would be a scorcher.

With the moorland and hillside farms behind her, Lacey entered the depths of the town. As she hurried along Towngate she was plunged into sudden gloom, the sun shut out by towering, soot blackened mills and the air thick, every crevice filled with the rank stink of raw wool, acrid smoke and foul smelling dyes. Behind the mills ran a tumbling river and the slick, still waters of a canal. Today, the canal added its own stink, the pungent reek wafting through the mill yards and into the street. Lacey’s nose wrinkled.

When she reached Turnpike Lane, a shabby little terrace of two up and two down houses, she darted up to number thirteen and rapped on the door. It opened instantly.

‘You’re late,’ Joan Chadwick exclaimed, slamming the door behind her. ‘We’ll have to dash if we’re to get there before the hooter blows.’ Joan hoisted her basket into the crook of her arm and set off at a run, Lacey keeping pace with her cousin.

At the end of Turnpike Lane they crossed the main road, dodging the constant stream of horse drawn carts and the new, motorised lorries that plied their trade between Liverpool, Manchester, Huddersfield and Bradford.

Lacey leapt for the pavement. ‘Phew, that were a bit close. You forget how fast them things can travel,’ she panted, as a huge lorry rumbled past, its horn blaring. She adjusted her basket then ran the last few yards to Brearley’s Mill, Joan hot on her heels. As they hurtled under the arched gateway a piercing shriek reverberated from the Mill’s tower; the six o’ clock hooter.

‘If tha’d a bin a second later tha’d a bin locked out,’ the wizened old gatekeeper shouted as they scooted past him. The ornate iron gates clanged shut, the gatekeeper deaf to the pleas of a woman left outside.

Lacey half turned. ‘Let her in, you mean old sod, it’s nowt to you,’ she shouted.

Joan threw the woman a pitying glance. ‘Thank God that wasn’t us,’ she said, both girls knowing had they been any later they too would have been locked out for the next two and a half hours. It was policy in all mills in the valley to punish tardy employees by keeping them out until breakfast time at eight thirty, thereby losing them a quarter of their day’s wages. Making a final dash across the cobbled yard, Lacey and Joan entered the weaving shed, the smell of linseed oil, sized warp and greased leather assailing their senses.

‘Whew! It’s hot in here,’ gasped Joan, flapping a hand under her nose as she followed Lacey into an alcove in the back wall of the shed.

‘It’ll get worse afore the day’s done,’ replied Lacey, undoing the buttons on her blouse. Joan followed suit, the girls stripping down to their underwear and at the same time keeping a sharp eye out for Sydney Sugden, the lecherous overlooker. The women in the weaving shed called him Slimy Syd, his proclivity for sexual harassment earning him the nickname. It wouldn’t do to let him catch them in a state of undress; he didn’t need encouragement.

Lacey was just tying the strings on her sleeveless, cross-over pinny, the sort most weavers wore to keep the fluff off their clothing, and Joan was wrapping hers across her plump little belly when Syd slunk from behind a loom, the disappointment at being too late plain on his face.

Syd stomped off, and the girls, giggling at having thwarted him, covered their heads with cotton headscarves to protect their crowning glories from the savage thrash of their looms or the overhead, low hanging leather belts attached to the drums and pulleys that powered them. Together, they hurried down ‘weaver’s alley’ – the wide space that separated row upon row of looms – and standing between the two looms she minded, Lacey called across the alley to Joan.

‘Syd’ll be as mardy as hell since he didn’t get a chance to see you in your knickers.’

Joan’s saucy reply was lost as the hooter blasted again, the shed echoing with a grinding roar as the weavers set their looms in motion. Shuttles trailing fine woollen yarns flew forwards then backwards, the strategy of advance and retreat interlacing wefts with warps, the beaters thrashing faster than the eye could see. Oblivious to the monotonous clatter, Lacey kept a constant lookout for broken threads, empty bobbins or flaws that might suddenly mar the fabric’s parallel perfection.

Golden shafts of sun pierced the shed’s glazed roof, descending through a haze of shimmering dust motes to glint on the oily machinery below, and as fine Yorkshire worsted smoothly lapped thickening cloth beams, the heat in the shed intensified.

A stream of sweat wormed its way under Lacey’s chin and trickled between her breasts. She plunged her hand inside her overall to wipe away the discomfort, withdrawing it just as quickly to catch and secure a loose end.

When Joan glanced in Lacey’s direction, Lacey raised two fingers to her lips indicating she was about to speak. Although the noise of machinery eliminated normal conversation, Lacey, like all weavers, was adept at mouthing and lip reading; in the cacophonous din of the weaving shed gossip flowed as easily as it would in the quiet of a churchyard.

‘Them windows need opening; I’m sweating cobs,’ mouthed Lacey, gesturing to the high transoms that ran the length of both sides of the shed.

‘Me an’ all; I’ll faint if it gets any hotter,’ Joan mouthed back.

Lacey watched out for Syd to ask him to open the windows, but the overlooker was nowhere to be seen. Typical, she thought; when you want him he’s never there.

At half past eight the hooter blew again, the looms shut down and mill hands poured out into the yard, hungry for breakfast. In the shade of the dye house wall, Lacey and Joan ate drip bread and drank cold tea. Half an hour later they were back in the hot, dusty confines of the weaving shed.

![]()

![]()

Born and raised in West Yorkshire, Chrissie trained to be a singer and cellist before becoming a teacher. When she married her trawler skipper husband, they moved to a little fishing village in N. Ireland. Chrissie is passionate about history and that passion and knowledge shine through in her writing. The Girl from the Mill is her debut novel.

Born and raised in West Yorkshire, Chrissie trained to be a singer and cellist before becoming a teacher. When she married her trawler skipper husband, they moved to a little fishing village in N. Ireland. Chrissie is passionate about history and that passion and knowledge shine through in her writing. The Girl from the Mill is her debut novel.