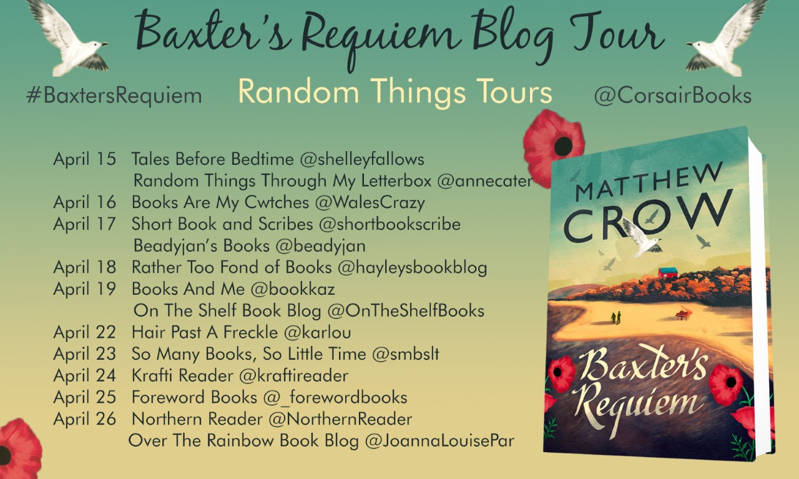

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Extract from Baxter’s Requiem by Matthew Crow @CorsairBooks #RandomThingsTours

I’m delighted to be able to share an extract from Baxter’s Requiem by Matthew Crow with you today as part of the blog tour. My thanks to Anne Cater from Random Things Tours for the place on the tour.

![]()

A tender, witty, uplifting story about friendship, family and community written with great humour that will appeal to fans of Rachel Joyce, Ruth Hogan and Joanna Cannon.

Let me tell you a story, about a man I knew, and a man I know…

Mr Baxter is ninety-four years old when he falls down his staircase and grudgingly finds himself resident at Melrose Gardens Retirement Home.

Baxter is many things – raconteur, retired music teacher, rabble-rouser, bon viveur – but ‘good patient’ he is not. He had every intention of living his twilight years with wine, music and revelry; not tea, telly and Tramadol. Indeed, Melrose Gardens is his worst nightmare – until he meets Gregory.

At only nineteen years of age, Greg has suffered a loss so heavy that he is in danger of giving up on life before he even gets going.

Determined to save the boy, Baxter decides to enlist his help on a mission to pay tribute to his long-lost love, Thomas: the man with whom he found true happiness; the man he waved off to fight in a senseless war; the man who never returned. The best man he ever knew.

With Gregory in tow Baxter sets out on a spirited escape from Melrose, bound for the war graves of Northern France. As Baxter shares his memories, the boy starts to see that life need not be a matter of mere endurance; that the world is huge and beautiful; that kindness is strength; and that the only way to honour the dead, is to live.

Baxter’s Requiem is a glorious celebration of life, love and seizing every last second we have while we’re here.

![]()

‘I’m afraid it’s not good news, Mr Baxter,’ the doctor said, as Baxter sat on the edge of his bed, polishing his glasses.

‘Nothing ever is at my age,’ Baxter replied with a short laugh.

‘What we’d be looking at now is making you comfortable.’

Baxter grunted, replaced his glasses on his head and stared grimly around the room. The walls had been painted a dappled magnolia, and above the bed there hung a crude picture of a country meadow which he found as offensive as the limp meals which were presented to him thrice daily.

‘It’s like practising being dead and paying for the privilege!’ he had announced upon arrival, as his belongings were laid out carefully and to his strict instruction.

He had insisted on bringing with him his record player, a collection of twenty-seven records and a boxful of framed black and-white photos that he instructed the staff to arrange along the windowsill in a very specific order. It was sentimentality which bound him to his small collections of keepsakes and memories, not necessity. If anything his memory was growing stronger with age. Once hazy recollections had become sharper as he himself began to blur at the edges. All he had to do was close his eyes and off he went.

‘Are you OK, Mr Baxter?’ asked the doctor, pulling Baxter’s attention back to the present.

‘Apparently not.’

‘No, well, quite. It’s a lot to digest. Would you like some time? Is there someone we can call for you?’

Baxter shook his head and smiled. ‘Do you know,’ he said, slowly raising his eyebrows, ‘I’m not entirely sure there is.’

Born the only child of a wealthy older couple, Baxter had found youth a bemusing chore and his peers a complete mystery. Then, when orphaned at twenty-one to an arthritic knee, a sensitive accelerator pedal and an inadequately signposted cliff-edge in Dorset, Baxter was thrust into a role he discovered he was made for: that of absolute independence.

Once he’d overcome the gaucheness of youth he developed an easy charm and a willingness for new experiences which endeared him to most people that he met. He made and kept friends both locally and around the world. But the past two decades had seen his social circle diminish incrementally in an inevitable carousel of overpriced wreaths, tuneless hymns and hastily defrosted vol-au-vents. Like some cosmic game of Guess Who? in which he would soon be the only character left.

‘Well, there are people we can arrange to come and talk to you.’

Baxter shrugged. ‘Nothing to say, really.’ ‘Like I said,’ the doctor went on, ‘at this stage there are plenty of things we can do to make you more comfortable.’

‘I haven’t been comfortable since I slipped a disc in eighty nine. Why start now?’

‘There is medication,’ the doctor tried.

At this, Baxter perked up. ‘Ooh, yes please!’ he said, pointing towards the prescription pad.

‘I always was partial to an opioid, none of this holistic nonsense you lot seem to be touting these days.’

The doctor, now very much at Baxter’s mercy, began fidgeting with the stethoscope around his neck.

‘We often find that the side effects of medication outweigh the symptoms they were prescribed to treat in the first place. . . ’

Baxter smiled. ‘Dear boy. I’m ninety-four years old. And according to your good self I am unlikely to experience the heady rush of ninety-five. What exactly are you worried will happen? Sweet angel Baxter, gone too soon . . . ’

‘There’s no reason why we can’t look at the possibility of medication alongside more, ah, therapeutic treatments,’ tried the doctor, gamely.

Baxter raised his hand the way he used to do in his classroom when the children were getting out of control.

‘I apologise for my outburst,’ Baxter said. ‘It was unfair and disrespectful, and for that I am sorry. But for God’s sake, boy, lighten up. Nobody my age sits down in front of a doctor and expects good news. Go off script . . . Relax,’ he said, with a gentle laugh. ‘It’s only life. You don’t always have to take it so seriously. Ask me something normal. Treat me like a human being. There’s a roomful of clues and conversational prompts at your disposal.’

‘Well, yes,’ said the doctor, as uneasy with Baxter’s sudden turnaround in mood as he had been with his initial trickiness.

There was a long silence.

‘Well?’ Baxter asked.

The doctor breathed in, scanned the room and widened his eyes apprehensively.

‘You going anywhere nice on your holidays this year?’ he tried, already shrugging in apology at his effort.

‘Bloody hell,’ Baxter said, shaking his head. ‘Never mind.’

‘Is there anything more I can help you with today, Mr Baxter?’

‘No. But thank you for your trouble. It has been a particularly gruelling morning. Sixteen across took me three cups of tea and left me with hand cramp from clutching the thesaurus.’

‘It’s brilliant that you’re keeping your mind active,’ the doctor said, only to be cut down by a look so sharp it could have shucked an oyster.

‘Right then,’ said Baxter. ‘I shall take a rest. Perhaps lie down with a spot of Mozart.’ He stood up and began rifling through his record collection. ‘Are you fond of music?’

‘I like jazz.’

‘So that’s a no then,’ Baxter said, crestfallen, returning his attention to his vinyl. ‘I was always partial to the blues myself. Soul music. And the old masters of course. But jazz . . . ’ He shuddered. ‘Waste of my time and theirs. If you can’t carry a tune then learn a fucking trade,’ he said with a laugh. ‘Don’t torture the rest of us with your atonal efforts.’

At this the doctor laughed too, more at the incongruity of such foul language from a respectable old man than anything else.

‘Each to his own, eh, Mr Baxter?’

Baxter found the record he was looking for, slid it from its sleeve and placed it on the turntable. The needle hit the groove and a rich melody filled the room like ink in water.

‘Thank you for your care and efforts,’ said the old man with a nod, as he returned to his perch on the side of the bed.

‘You take care of yourself,’ the doctor said as he left the room, ‘and don’t forget to rest.’

‘With less than a year left I don’t see how I can rest,’ Baxter said, lying back on the bed, lifting his legs onto a pillow at the end of the mattress. ‘There’s so much I’ve yet to do.’

‘All in good time, Mr Baxter.’ The Doctor said, gently closing the door too and leaving the old man to it.

‘It’s the most lucrative currency of all, time,’ said Baxter to nobody in particular, his voice deepening as his body began to sink into his mid-morning nap. ‘We must be sure to invest wisely.’

![]()

![]()

Matthew Crow was born and raised in Newcastle. Having worked as a freelance journalist since his teens he has contributed to a number of publications including the Independent on Sunday and the Observer. He has written for adults and YA. His book My Dearest Jonah, was nominated for the Dylan Thomas Prize.

Matthew Crow was born and raised in Newcastle. Having worked as a freelance journalist since his teens he has contributed to a number of publications including the Independent on Sunday and the Observer. He has written for adults and YA. His book My Dearest Jonah, was nominated for the Dylan Thomas Prize.

Huge thanks for supporting the blog tour Nicola – I love this book!