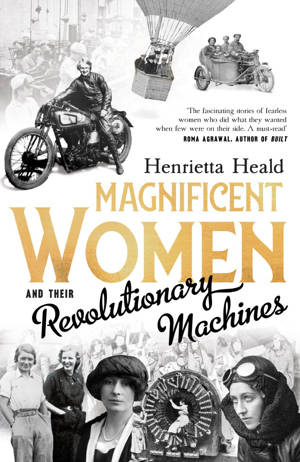

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Extract from Magnificent Women and Their Revolutionary Machines by Henrietta Heald @henrietta999 @magnificentwom @unbounders #MagnificentWomen #RandomThingsTours

Welcome to my stop on the tour for Magnificent Women and Their Revolutionary Machines by Henrietta Heald. I have a fabulous extract to share with you today. My thanks to Anne Cater from Random Things Tours for the place on the tour.

![]()

‘Women have won their political independence. Now is the time for them to achieve

their economic freedom too.’This was the great rallying cry of the pioneers who, in 1919, created the Women’s Engineering Society. Spearheaded by Katharine and Rachel Parsons, a powerful mother and daughter duo, and Caroline Haslett, whose mission was to liberate women from domestic drudgery, it was the world’s first professional organisation dedicated to the campaign for women’s rights.

Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines tells the stories of the women at the heart of this group – from their success in fanning the flames of a social revolution to their significant achievements in engineering and technology. It centres on the parallel but contrasting lives of the two main protagonists, Rachel Parsons and Caroline Haslett – one born to privilege and riches whose life ended in dramatic tragedy; the other who rose

from humble roots to become the leading professional woman of her age and mistress of the thrilling new power of the twentieth century: electricity.In this fascinating book, acclaimed biographer Henrietta Heald also illuminates the era in which the society was founded. From the moment when women in Britain were allowed to vote for the first time, and to stand for Parliament, she charts the changing attitudes to

women’s rights both in society and in the workplace.

![]()

One

Leading Ladies

On 23 June 1919, seven exceptional women gathered at 46 Dover Street in London’s Mayfair to do something that had never been done before – to create a professional organisation dedicated to campaigning for women’s rights. It was the official birth of the Women’s Engineering Society, the fruit of an idea conceived several months earlier, as the guns of the Great War fell silent.

Each of the seven women was required to sign a document giving her name, address and marital status. Outside the inner circle, but keeping a eagle eye on its every move, was Caroline Haslett, a young electrical engineer and former suffragette, who earlier that year had been appointed the society’s first administrator.

At the head of the table was Katharine, Lady Parsons, a commanding and charismatic figure, who gave her address as 6 Windsor Terrace, Newcastle upon Tyne. Katharine was the wife of the revered engineer Sir Charles Parsons, whose development of the steam turbine had changed history by revolutionising the propulsion of ships and providing the means for the cheap and widespread generation of electricity. In 1927 Charles Parsons would be admitted to the Order of Merit, an honour in the personal gift of the sovereign.

From the early days of their marriage, Katharine had been immersed in her husband’s work, supporting the creation of his engineering works at Heaton and Wallsend, east of Newcastle, in the 1880s and 1890s. She had championed the employment of women in engineering and shipbuilding during the war, and delivered an influential speech in 1919 highlighting this phenomenon.

The first signatory in the group was Eleanor, Lady Shelley-Rolls, a keen balloonist, the sister of the late Charles Rolls, with whom she shared a passion for speed and danger. Charles had partnered Henry Royce in a fabulously successful automobile production business, set up in 1906, until he was killed in a flying accident four years later, at the age of thirty-two. After the death of her two remaining brothers during the war, Lady Shelley-Rolls became heir to a large fortune and the Hendre, the family mansion and estate in Monmouthshire. On her marriage in 1898 to Sir John Shelley, a great-nephew of the poet Shelley, the couple changed their name to Shelley-Rolls.

The youngest founder, and one of only two in the group identified as ‘spinsters’, was thirty-four-year-old Rachel Parsons, the sole surviving child of Charles and Katharine Parsons, who was living at her parents’ London address, 1 Upper Brook Street, near Hyde Park – having left behind early in the war her familiar haunts in northeast England. In 1910 Rachel had become the first woman to study Mechanical Sciences at Cambridge University. During the war she had served briefly as a director of her father’s firm at Heaton before joining the training department of the Ministry of Munitions. Her brother Algernon, her only sibling, had died just over a year earlier in action on the Western Front.

Janetta Mary Ornsby was the wife of Robert Embleton Ornsby, a mining engineer at Seaton Delaval colliery in Northumberland, where he became resident agent and later qualified as a manager of mines.

The Ornsbys lived at 7 Osborne Terrace, Jesmond, a short distance from Windsor Terrace, the Newcastle home of the Parsons family.

The second spinster in the group was Margaret Rowbotham, who gave her address as: c/o The Galloway Engrs. Co. Ltd, Kirkcudbright. Margaret had studied mathematics at Cambridge before training and working as a maths teacher. But her real passion was motor engineering, and she spent several months training at the British School of Motoring in workshop practice and driving, at the end of which she was the proud possessor of a Royal Automobile Club Driver’s Certificate. In 1917 Margaret had become works superintendent at the Galloway Engineering Company at Tongland in the southwest corner of Scotland, where the workforce was largely female.

The woman with the grandest address was Margaret, Lady Moir, of 54 Hans Place, Knightsbridge – but, in spite of her position of apparent privilege, Margaret Moir had worked during the war as a lathe operator in a munitions factory. As the wife of the prominent Scottish civil engineer Sir Ernest Moir, in whose bridge-building, tunnelling and harbour projects she took a keen interest, she liked to describe herself as ‘an engineer by marriage’.

By contrast with the others in the group, Laura Annie Willson had grown up in poverty. Having started work in a textile factory in Halifax, west Yorkshire, at the age of ten she became a campaigner for workers’ rights and a suffragette, and was twice imprisoned for her political activities.2 After her marriage in 1899 to George Willson, she and her husband jointly ran a machine-tool factory in Halifax, which favoured the employment and training of women. Laura Annie had received an MBE for her wartime munitions work, and she would go on to design and build hundreds of houses for working people, some of them equipped with electricity, in Halifax and in two towns in Surrey.

In the normal course of events, the paths of these seven women would have been unlikely to cross, but they had been drawn together by their wartime experiences and by trenchant opposition to a parliamentary bill that sought to outlaw the employment of women in engineering. They relished the strides towards gender equality that had been made during the war – especially the opportunities that had opened up for female technical education – and were determined to preserve those hard-won advantages.

![]()

![]()

Henrietta Heald is the author of William Armstrong, Magician of the North which was shortlisted for the H. W. Fisher Best First Biography Prize and the Portico Prize for non-fiction. She was chief editor of Chronicle of Britain and Ireland and Reader’s Digest Illustrated Guide to Britain’s Coast. Her other books include Coastal Living, La Vie est Belle, and a National Trust guide to Cragside, Northumberland.

Henrietta Heald is the author of William Armstrong, Magician of the North which was shortlisted for the H. W. Fisher Best First Biography Prize and the Portico Prize for non-fiction. She was chief editor of Chronicle of Britain and Ireland and Reader’s Digest Illustrated Guide to Britain’s Coast. Her other books include Coastal Living, La Vie est Belle, and a National Trust guide to Cragside, Northumberland.

Discover more from Short Book and Scribes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

thanks for the blog tour support Nicola x