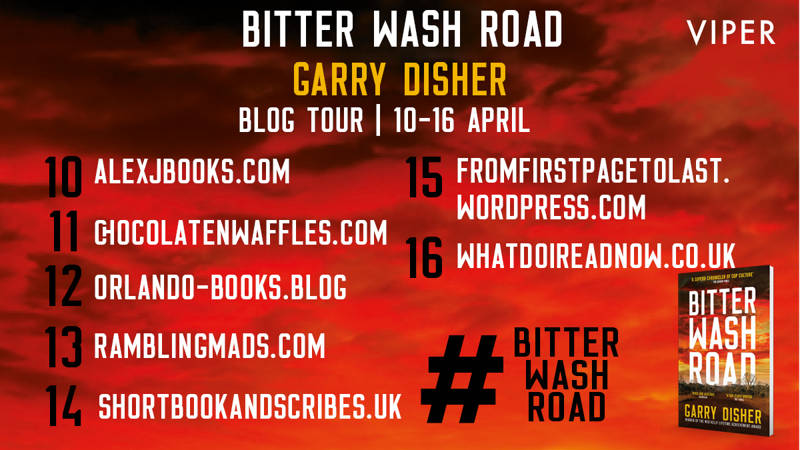

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Extract from Bitter Wash Road by Garry Disher @ViperBooks

I’m so pleased to be sharing an extract from Bitter Wash Road by Garry Disher with you today as part of the blog tour. My thanks to Rachel Nobilo from Viper Books for the place on the tour.

ONE DEAD-END POSTING. ONE DEAD BODY.

A TRAGIC ACCIDENT? THAT’S WHAT THEY WANT YOU TO THINK…Constable Paul ‘Hirsch’ Hirschhausen is a whistle-blower. Formerly a promising metropolitan detective, now hated and despised, he’s been exiled to a one-cop station in South Australia’s wheatbelt. So when he heads up Bitter Wash Road to investigate gunfire and finds himself cut off without backup, there are two possibilities. Either he’s found the fugitive killers thought to be in the area. Or his ‘backup’ is about to put a bullet in him.

He’s wrong on both counts. But Tiverton – with its stagnant economy, entrenched racism and rural isolation – has more crime than one constable can handle. And when the next call-out takes him to the body of a sixteen-year-old girl, it’s clear that whether or not Hirsch finds her killer, his past may well catch up with him.

Winner of the German Crime Prize, this new novel from Ned Kelly Lifetime Achievement Award-winner Garry Disher is the gold standard for Australian noir.

3

Hirsch’s first thought was: Pullar and Hanson, the kids were right, and he felt a kind of dismay mingled with excitement.

‘Suspicious?’

‘Probable hit-and-run.’

Hirsch made the mental adjustment: not Pullar and Hanson. ‘Nancarrow?’

‘No. He claims he stopped by the road for a leak, saw a dead woman lying in the dirt.’ Kropp paused and added, ‘Dr McAskill’s on his way up there.’

‘I’m on it, Sarge.’

Hirsch placed the handset in the cradle. The women and their children were watching him from the veranda. ‘Got to go,’ he called, climbing behind the wheel. He got a nod for his pains, a couple of half-hearted waves.

Pausing at the front gate, Hirsch fed ‘Muncowie’ into the GPS. It directed him not back to the highway, as he’d expected, but further out along Bitter Wash Road, which eventually made a gradual curve to the north, smaller roads branching from it. One of them looped west onto the Barrier Highway a short distance north of Muncowie.

It was a shorter route, Hirsch could see that from the map. Unsealed for most of the distance.

After twenty minutes, he found himself skirting around the Razorback, driving through red dirt and mallee scrub country, the road surface chopped and powdery where it wasn’t ribbed with a stone underlay. Very little rain had fallen here last night; it was as if a switch had been flicked, marking the transition from arable land to semi-desert.

Leasehold land, one-hundred-year leases defined by sagging wire fences, sand-silted tracks and creek beds filled with water-tumbled stones like so many misshapen cricket balls.

You might find a fleck of gold in these creek beds if you were lucky, or turn your ankle if you were not. It was land you walked away from sooner or later: Hirsch saw a dozen stone chimneys and eyeless cottages back in the stunted mallee, little heartaches that had struggled on a patch of red dirt and were sinking back into it.

Ant hills, sandy washaways, foxtails hooked onto gates, a couple of rotting merino carcasses, a tray-less old Austin truck beneath a straggly gumtree. Weathered fence posts and the weary rust loops that tethered them one to the other. He saw an eagle, an emu, a couple of black snakes. It was a land of muted pinks, browns and greys ghosted by the pale blue hills on the horizon.

That was what he saw. What he didn’t see, but sensed, were abandoned gold diggings, mine shafts, ochre hands stencilled to rock faces. A besetting place. It spooked Hirsch.

The sky pressed down and the scrub crouched. ‘It’s lovely out there,’ one of the locals had assured him during the week, waiting while Hirsch witnessed a statutory declaration.

He passed in and out of creek beds and saw a tiny church perched atop a rise. What the fuck was it doing there, this shell of a church? Ministering to other stone shells, he supposed, left by the men and women who’d settled here and failed and walked away.

Hirsch fought the steering wheel, the gear lever, the clutch. His foot ached. Even the HiLux struggled, pitching and yawing inflexibly, taking him at a crawling pace through the back country. You had to hand it to technology, the GPS giving him the shortest route but blithely unaware of local conditions. It would take him forever to reach Muncowie at this rate, longer if he holed the sump or punctured a tyre.

Then he was out on the highway. Muncowie 7 according to the signpost. He made the turn, heading south, the valley less obvious here, the highway striping a broad, flat plain. It gave Hirsch a sense of riding high above sea level, the sky vast and no longer pressing down, the hills a distant smear on either side. Meanwhile the crops, stock and fences were marginally better than the country he’d just passed through, more and greener grass, less dirt, as if he’d passed across the rain shadow again, moved from unsustainable life to a fiftyfifty chance of it.

And then in the emptiness he saw another car. Black. It drew closer.

Not a Chrysler. A Falcon, he saw as it passed.

Hirsch thought about Pullar and Hanson. In terms of timing, geography and logic, it wouldn’t make sense for them to have headed down here. Travel two thousand kilometre in a reasonably distinctive vehicle, away from the country they knew? Hirsch couldn’t see it. But he could see how the men might hunt in a place such as this. They had been preying on roadhouse waitresses along the empty highways, housewives and teenage daughters on lonely country roads.

It had started as a local backblocks story, a Queensland story—albeit a vicious one—which quickly went viral when Channel Nine muscled in, giving the killers a voice. Back in August a forty-year-old Mount Isa speed freak named Clay Pullar and an eighteen-year-old Brisbane cokehead named Brent Hanson raped and murdered three roadhouse waitresses over a two-week period. Police tracked the men to a caravan park in northern New South Wales but arrived too late. They found the body of a Canadian hitchhiker roped to a bed. Further sightings placed the men in Cairns, Bourke, Alice Springs, Darwin . . . Nothing definite until they broke into a farmhouse near Wagga, where they raped a teenager in front of her trussed-up parents and fled north with her to a property across the border and along the river at Dirranbandi.

Feeling pleased with himself, Pullar phoned Channel Nine on his mobile phone. He’d just managed to prove who he was when the signal failed, so Channel Nine dispatched a reporter and a cameraman by helicopter, which set down on the back lawn long enough to leave a satellite phone, and took off again, circling overhead. Pullar appeared. Even through the long pull of the camera lens he looked tall, gaunt, hard, insane. He grinned and waved, showing stumpy teeth, grabbed the phone, returned to the farmhouse, and began to explain himself. An exclusive, a live interview, you couldn’t ask for better. Fuck ethics, the public had a right to know. Fuck sense, too; Pullar made absolutely no sense but was full of frothing lunacy.

The police took thirty minutes to arrive. They surrounded the house, jammed the signal, chased the helicopter away—and waited. Night fell. They tried to talk to Pullar and Hanson. After a few hours of silence it occurred to them to rush the house . . .

They found an elderly man and woman unconscious and the Wagga teenager naked and traumatised. No sign of Pullar and Hanson, who had fled, on foot, to a neighbouring property where they stole a beefy black Chrysler 300C station wagon.

By daybreak they were hundreds of kilometres north, apparently heading for Longreach. Another rape-and-murder team might have swapped the Chrysler for a less obvious car at the earliest opportunity; Pullar, back on the phone to Nine, had said, ‘Man, this car has got some serious grunt.’

Garry Disher is one of Australia s best-known novelists. He s published over forty books in a range of genres, including crime, children s books, and Australian history. His Hal Challis and Wyatt crime series are also published by Soho Crime. He lives on the Mornington Peninsula, southeast of Melbourne.

Discover more from Short Book and Scribes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.