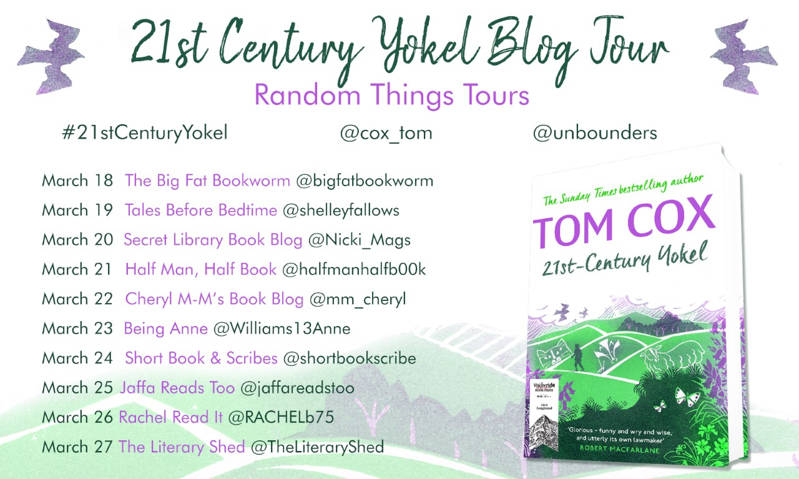

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Extract from 21st Century Yokel by Tom Cox @cox_tom @unbounders #21stCenturyYokel

Welcome to my stop on the blog tour for 21st Century Yokel by Tom Cox. I have a fabulous extract from chapter one to share with you today. My thanks to Anne Cater from Random Things Tours for the place on the tour.

![]()

Longlisted for the Wainwright Golden Beer Book Prize

21st-Century Yokel is not quite nature writing, not quite a family memoir, not quite a book about walking, not quite a collection of humorous essays, but a bit of all five.

Thick with owls and badgers, oak trees and wood piles, scarecrows and ghosts, and Tom Cox’s loud and excitable dad, this book is full of the folklore of several counties – the ancient kind and the everyday variety – as well as wild places, mystical spots and curious objects. Emerging from this focus on the detail are themes that are broader and bigger and more important than ever.

Tom’s writing treads a new path, one that has a lot in common with a rambling country walk; it’s bewitched by fresh air and big skies, intrepid in minor ways, haunted by weather and old stories and the spooky edges of the outdoors, restless and prone to a few detours, but it always reaches its destination in the end.

Or support your High Street with Hive.

![]()

WITCHES’ KNICKERS

January. Haldon Hill, the border hill. Such a long, high wall in the sky as you approach it from the north-east, so thick with trees, always a tiny bit surprising that a few minutes later you can be on top of it in a car. Also surprising, perhaps, to my car itself, which lets out a harassed groan as I change gear for the final ascent. My ears pop hard as I reach the brow. It happens every time. When I’ve told hardy natives of the South West Peninsula the same thing, they have sometimes claimed I’m being overdramatic but I’m honestly not. Maybe it’s because my sensitive eustachian tubes spent too many years living closer to sea level, in a more recumbent landscape, but the altitude is too much for them. ‘Ppppop!’ they go, as always, maybe even a bit louder than usual today. What that noise signifies to me is that I have entered the unofficial country that I call home, comprising Cornwall and the western two thirds of Devon.

Haldon rises, dividing the land, around six miles south-west of Exeter, which has always struck me as the most sarcastically named of small cities: a place that, when you’re attempting to get out of it at rush hour, appears to have no exit at all. If you look at it another way, though, the name is apt. When you reside on the west side of Haldon Hill, as I do, Exeter feels like your exit to the rest of Britain: the beginning of that place which, when you’ve lived down here for any time at all, you start to think of as Everywhere Else. Draw a line directly south from Haldon’s summit and you reach the exact point where the cliffs change colour – soft sandy red giving way to gnashing dark grey. Haldon seems like a barrier and must have seemed an even bigger one before it was tarmacked over with dual carriageway. Evidence of several sunken medieval lanes ascending the hill has been found on its east side, but almost none on its western slopes. Weary fourteenth-century travellers from the east would arrive at Lidwell Chapel near the eastern base of Haldon and receive offers of hot food and a bed for the night from Robert de Middlecote, the monk who lived there. Middlecote would then drug them, cut their throats and dump their bodies in the well in the chapel’s garden – allegedly bottomless, like so much still water in folklore. ‘Ooh, bloody hell, I’m not going over that,’ you can imagine similarly weary Romans exclaiming, thirteen hundred years or so earlier, as Haldon came into view. ‘We’ve done enough conquering, anyway. Let’s just leave whoever lives over there to carry on cuddling boulders and worshipping trees, or whatever it is they do.’ The Deep South West was its own country then and remains so now. Making a home in it is still a commitment to a certain kind of life, with more potential to be a self-contained part of its own immediate surroundings. Pass over that long brow and the land begins to steepen and get more intimate with itself, employment becomes more scarce, communities become more scattered and the idea of a day trip to the middle of the country becomes more fatigue-inducing.

As often as not, you drive up to the top of Haldon in one kind of weather and descend in another. In Exeter today there’s been squally showers and the lingering grey of a collective tetchy mood, but as I come down the opposite side, the sun switches on its spotlight function and illuminates the valley. Dartmoor streaks away in front of me on the right, unearthly and moody and promising and electric. They say in Devon that if you can’t see the moor, it means it’s raining, and if you can see it, it means it’s about to rain. That’s a comic exaggeration, of course, but not a huge one. Today the moor looks like a giant outdoor factory where witches make weather. There are countless small bright gaps in the sky, like holes stabbed in a tent roof to let the light in, then longer, bigger, more jagged gaps, as if the person in the tent has lost patience and gone at it with a bread knife. Some hills are enigmatically yellow in a way that doesn’t seem to correspond with the cloud above them, others a dark green verging on black that’s no less confusing. I can’t get nonchalant about this view, and it’s become even more fascinating to me as I’ve become more intimate with the moor. I will glance across and try to work out which shape or shade might denote a patch where I’ve walked. Is that where the farm is that I walked past that time with the huge ball of wire outside with the variety of animal skulls placed in it? I will think. No. Perhaps that’s a couple of miles further north. Maybe it’s the wildflower meadow I was pursued across last April by a small, determined pig.

I press on past Heaven and Hell Junction, Heaven being the moor and Hell staring it down from across the tarmac in the form of Trago Mills, the vast, grotesque shopping and leisure park whose toxic-waste-dumping, UKIP-supporting, wildlife-shooting owners the Robertson family once printed adverts calling for the castration of gay men. Up another big hill, past Ashburton Junction One and Ashburton Junction Two – the one which looks like my junction, that I take by mistake when I’m tired – and I’m home, or as good as, heading seawards on the smaller road where home begins in the most graspable sense: a zigzagging one, full of roller-coaster dips and climbs. To the right of the road is the River Dart and, because the road attempts to use the river as its guide, it is at the constant mercy of its indecision. All the Dartmoor rivers are capricious, but none that race down from the moor prevaricate about their route more often than the Dart. The hills here are not like those in Somerset or east Devon, which have wide valleys and plains between them; they are a community, bunching together as if nervously fearing solitude. The Dart finds the tight rare spaces between them and curls around them at flamboyant length, making its scenic way to the ocean.

And if you’d like to read the rest of chapter one then click here.

![]()

![]()

Tom Cox lives in Devon. A one-time music journalist he is the author of the Sunday Times bestselling The Good, the Bad and the Furry and the William Hill Sports Book longlisted Bring Me The Head of Sergio Garcia. Help the Witch, a collection of folk ghost stories, will be published in October 2019.

Tom Cox lives in Devon. A one-time music journalist he is the author of the Sunday Times bestselling The Good, the Bad and the Furry and the William Hill Sports Book longlisted Bring Me The Head of Sergio Garcia. Help the Witch, a collection of folk ghost stories, will be published in October 2019.

Discover more from Short Book and Scribes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks so much for supporting the Blog Tour Nicola x