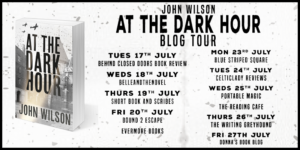

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #GuestPost by John Wilson, Author of At the Dark Hour @fayerogersuk @authoright

Welcome to my stop on the blog tour for At the Dark Hour by John Wilson. I have a great guest post from the author about how he did his research for the book. My thanks to Faye Rogers for the place on the tour.

![]()

A moving story about the nature of love and redemption set amidst the worst of the London Blitz and the destruction of London’s hallowed seat of law, the Temple

Adam Falling is a failing, sick barrister married to Catherine but conducting an affair with the glamorous Julia, who happens to be the wife of his Head of Chambers, Jeremy Pemberton.

Julia, fearful of losing her children, suddenly ends the affair. But it is too late. Pemberton discovers it and Adam is kicked out of his home and his chambers. Unable to work without a chambers and facing ruin, salvation comes in the unlikely form of the brilliant barrister, Roland (“Roly”) Blytheway. Blythway, held back in his career because of his sexuality, befriends him and invites him to join his chambers at Lamb Building.

It is there he finds himself defending a Czech refugee, Tomas Novak, who has been accused of treason and who is facing the gallows and becomes mired in another contested divorce case for one Arnold Bateman, where he, on the recommendation of Pemberton, represents the co-respondent whilst Pemberton represents the petitioner – a piece of cruel psychological torture on the part of Pemberton.

Whilst the Blitz rages on around, can Adam save Novak from the gallows? Can he get Bateman off? Will he ever discover why Julia suddenly broke off their affair? Can he succeed in resisting Jeremy’s claims against him personally? He has been told that only one man can possibly save him and that man is Roland Blytheway.

At the Dark Hour is the story of ordinary people caught in the horror of war whilst the city is destroyed around them. It features many of the most notable real life events of the Blitz such as the bombing of the Café de Paris.

![]()

HOW I RESEARCHED AT THE DARK HOUR BY JOHN WILSON

Before I came down from Cambridge and went to study for the Bar I had rarely been to London. I come from Wigan and, although I studied law at Cambridge, I was unprepared for the splendour of the Temple. I learnt that the Temple Church had been consecrated in 1185 and was the home of the Knights Templar who had conducted their crusades from there. I leant how they had become immensely wealthy through these crusades and then had been violently suppressed by various kings who wanted their wealth, relying on all sorts of allegations such as the illicit kissing of Christ’s groin on the crucifix.

Walking about this wonderland which was the Temple I could see around me (they are still there now) all the signs of the devastation wreaked on the area by the Blitz during the Second World War. There was a plaque on the ground where Lamb Building used to be. A plaque where Fig Tree Court used to be and the Latin lettering over Cloisters told us that it had been reconstructed in 1952.

I was very curious about all of this – and about the history of the Templars generally. I became editor of the Inner Temple Students’ magazine, Pegasus, and decided to write an article about the Temple and the Blitz (which was its eventual title). I climbed up into the galleries of the Inner Temple Library and found all these monographs from long dead and long forgotten barristers which told of their own personal experiences of the Temple during the Blitz and I drew on them to write my article. These monographs have all gone now, having been moved into the archives. When, subsequently, I came to research At the Dark Hour (“ATDH”) I read, I think, most of the available literature on the Blitz and London. It became clear to me that all of these eminent historians had either ignored these sources or (more likely and understandable) were unaware of their existence. I thought at the time that the story of the destruction of the Temple would make an interesting tale to tell but I was a busy junior barrister and I had nothing to hook this on to.

A few years later, in a story too long to tell, I found myself writing and presenting a series of radio progammes for the BBC on young people leaving home and the legal battles that they faced. My first producer worked primarily for Women’s Hour and, when the series was updated a year or so later, my second producer specialised in radio plays. After we were done he left me a voice-mail message asking me to write some radio plays (on a subject of my choice) so that he could produce them for radio. I agreed to do so but I was a busy junior barrister (etc) and so I never found the time to do it. In addition, there was no internet so that research was difficult. However, I had conceived the idea of writing plays based upon real life treason trials during the Second World War. That idea stuck with me and I could see how this might possibly link in with a story about the destruction of the Temple during the Blitz.

At about that time my chambers moved out of the Temple to Gray’s Inn and then to Bedford Row just off the Theobalds Road so I lost touch with the world that was the Temple. By 2001 I was concentrating on family law, or divorce law. In 2002 I left my set to move back to the Temple.

My move brought me back to the Temple. All of my ideas about writing a story based upon the Blitz and upon treason trials were rekindled. But that still did not amount to a story that anyone would necessarily want to read.

Now I was a divorce lawyer although I had done many other things in the past. In the late 1980s I had conducted very large trials at the Old Bailey when I was still in my twenties. In particular, I had conducted a four-week vice trial. Rather dramatically, my client – who had been held in solitary confinement for his own safety – tried to commit suicide just before the start of the day’s business in court. He had managed to smuggle a small piece of string into his cell and then he had tied it extremely tightly around his neck. Then he had tied his tie equally tightly around his neck but with the knot at 180 degrees to the knot on the string. His attempt at suicide was discovered just before the day’s business was to begin. The warders had to cut him free. All hell broke loose and I was called out from counsels’ row to the holding room behind the dock to see my client with a terrible red wheal around his neck. The trial continued and I got him off. I used the attempted suicide in the novel with the character Tomas Novak replacing my client in the vice trial.

In my researches for the original article I learnt all sorts of other things. I learnt for example about the Alienation Office where refugees from Nazi Germany and across Europe were processed and I thought that I could use that as well.

My ideas began to grow into something more of a story. I knew that it needed to be meticulously researched but I also knew that, on my return to the Temple, what was missing was a love story. Being an unrepentant romantic I eventually realised what was missing from the bones of my story. Now that I was back in the Temple and specialising in divorce law I realised that what was needed was a love story. In fact, I ended up with several.

I called my heroine “Julia”. This was because of a long-standing fascination with that name which arose out of two literary characters particularly. The first was Julia Flyte from Brideshead Revisited and the second was Winston Smith’s lover in George Orwell’s 1984.

I had always had this notion in my mind that there were gradations of love. That no matter how much someone loved you they might love someone else more. That brought me on to thinking about what would happen if a woman loved a man to whom she wasn’t married but she loved her children more than she loved him. Can you love two people? I think that the answer is yes but, when it comes to the sticking point, you will love one or more people more than you love that other person. And, in those circumstances, do you even love the other person at all? This thought was very much in my mind when I wrote the novel.

But I still had it in mind to write a treason trial. I saw that treason represented betrayal on a “macro” scale whereas adultery represented betrayal on a “micro” scale. I saw that the two were thematically linked. And I could set both broad stories against the backdrop of the destruction of the Temple by the Blitz. Better than that, I could use the destruction of the Temple as a metaphor for my main character, Adam Falling’s, physical and moral collapse.

I had already learnt a lot about what happened in 1940 / 1941 – I had read nearly everything and a lot of things that the historians had missed. But that wasn’t enough. There were all sorts of things that did not make it into the formal histories. How much did it cost to have sex with a prostitute in 1940? I asked an old boy I knew very well and he said “ten bob”.

Who was actually left in the Temple when the war broke out? I asked my former director of studies at Pembroke College, Cambridge over a formal dinner in the college. He had been awarded the Military Cross and, despite his encyclopaedic knowledge and memory, professed not to remember why. I only found why he got it after his death. In answer to my question he said “the halt and the lame”. So, my hero had to be sickly. I had read virtually everything that George Orwell had ever written and I knew that he had applied to join up when the Second World War broke out but had been turned down on the grounds of his poor health. It transpired that Orwell was suffering from tuberculosis which killed him in 1950. So, I decided that Adam Falling would be in his late thirties and suffering from undiagnosed tuberculosis. I did a lot of online research into tuberculosis so that I could understand how the disease operated and progressed.

I was very fortunate to meet and know people of the generation who lived through this period. One of those was Daphne Sharp. Daphne remembered the Blitz. She remembered how members of the Bar would rifle through the wreckage of their chambers after a bombing raid looking for their papers and their books. I was able to use that. She also remembered that fresh eggs were so rare that, coming from Ireland with a collection of fresh eggs, one would cover them in nail varnish to ensure that they did not break in transit. I was not able to use that but I was able to create some drama, surrounding the final breakdown of Adam’s marriage to Catherine about the value of fresh eggs. Daphne is sadly now long departed.

Another old friend who is still alive and in his early eighties now is one of the brightest people I know. He came to England in May 1940 as a Hungarian Jewish refugee. He kindly read my manuscript and told me that gentlemen did not wear belts but would use buttoned on braces. He also told me that you could buy cigarettes under the counter at Weingotts in the Strand although I could not use that. He told me that it was not done for old soldiers to wear their medals to cocktail parties and so, with a stroke of the pen I took everyone’s medals off.

He was one of only two people that recognised the Renshaw libel trial which is described in the book. This was based on a very famous (at the time) libel case brought by the Sitwell siblings which was heard at the height of the Blitz. They felt that their literary standing and reputation had been called into question and sued. The High Court had to decide upon the literary merits of their works whilst bombs were falling all around and the future of England itself was in jeopardy. They won. I think it merited an editorial in the Times about the English spirit.

Of course, I read the Times archive avidly. I think I read about nearly every day of the period in the Times. In that way, I would know what time the sun rose or set. I would know about the reported news. When I mention news-sellers reporting victories in Libya this was because that was what the papers were saying on the day in question. When I wrote of a civic official destroying the gates of Lincoln’s Inn Fields with an oxyacetylene lamp that was, again, because that is what had happened on that day.

I realised, too, that the newspapers were heavily censored for understandable reasons. For example, whereas everyone in London knew about the bombing of the Café de Paris in March 1941, it was not widely reported. Therefore, I researched a very significant number of diaries that had been created at the time and had been posted in recent years on the internet. This helped me to understand the “disconnect” between what had happened and what everyone who was there actually knew. I was able to use this “disconnect” as a dramatic point: everyone knew what had happened, notwithstanding the reticence of the press and so a character, Catherine, could know of the bombing of the Café de Paris but could not know of its personal consequences.

The plot involved an apparent attempted bombing of London’s water systems in order to poison the populace. I therefore needed to understand the water systems. I was able to learn a certain amount from the Times Online archive and from Wikipedia. But it was not enough. There was a “stub” on Wikipedia making reference to a book about the history of the London Metropolitan Water Board. I was able to google around and find a copy which I ordered. It was delivered to my house in the South of France a few days later. It had belonged to the former head of the London Metropolitan Water Board in the 1950s. He signed his name in the frontispiece with a flourish and turned over the corner of the only page that had mentioned his name. I looked him up in the Times and discovered that he had died in the early 1970s so that this book had been languishing since that time. I doubt many people have read it.

I became increasingly conscious of the unfair and misogynistic nature of the divorce laws at that time. I was writing the chapter of a text book nominally entitled “The Married Women’s Property Act 1882”. I changed the title to bring it up to date but I did research the genesis of the Act which brought me into contact with the remarkable story of Lady Caroline Norton. I thought to myself that this would make an admirable basis for a book but someone beat me to that one. But I saw how the nature of the law could be, first of all, so unfair to women and, secondly, could encourage dishonesty. For, the last thing a woman could allow was to be found guilty of adultery – she would lose her children and any financial support. I didn’t know enough about adultery trials. Were they held with a jury for example? I didn’t know so, with the assistance of a good friend of mine, I emailed Professor Stephen Cretney, a very eminent family law scholar, who was able to confirm to me that they were not.

Thoughts of misogyny brought me on to considering the unfair treatment of homosexuals. I have many gay friends and some of them are the brightest, wittiest and kindest people I know. I therefore wanted to highlight this issue as well. I had read The Fatal Englishman by Sebastian Faulks (which told the story of Jeremy Wolfenden, a gay spy and known as “the cleverest boy in England”. His father was chair of the Wolfenden Report which, in the 1950s recommended the legalisation of male homosexuality. Jeremy Wolfenden died at the age of 31 in suspicious circumstances in Washington) and, of course, the trials of Oscar Wilde and so I wanted to add that into the mix.

What was the flavour and smell of London during the Blitz? I wasn’t there so I had to use my imagination. I was greatly assisted with the works of Graham Greene and, in particular, the End of the Affair and the Ministry of Fear.

What of the spies and the treason trials? I had not been able to research these when I had been offered a commission to write some plays about them. There was very little on the internet – although there was the intriguing detail that a person executed for treason did not have the benefit of a death certificate. So, my wife, Sue, and I went to the Imperial War Museum to try and find out. The limited evidence suggested that we were picking them up as soon as they landed. I suspect that this was because we had broken German codes. I used this in the novel for dramatic effect. I suspect that I have not found out the whole story here and that more will emerge with time.

I remained anxious to get the flavour of the period. The irony of the fact that certain parts of Mayfair and Islington were decidedly working class if not downright seedy. I did a lot of research into the small adds in the Times to find out more about this. I would also look at the larger adds. So that when, towards the end of the novel, Julia puts on a coat that she bought from Bradleys of Chepstow Place the previous season for twelve and a half guineas that is because it had, indeed, been on sale there that season at that price. There is a pencil drawing of it – shells embroidered on the pockets – in the Times.

Whilst writing this novel my mother died, in November 2004. I learnt subsequently that she had been working with the Code-Breakers at Bletchley Park. Subsequent to that I learnt that my dad’s reticence about his own work during the war was down to the fact that, after a first tour with Bomber Command, he had been transferred to Halifax 624 Squadron which basically did “special ops” and he was not allowed to speak about it. President Hollande of France awarded him the Legion d’Honneur last year.

I think that, finally, this novel is about secrets. Whether they are secret histories or secret loves sometimes they are uncovered and sometimes they are not.

Thank you, John, for such a full and interesting post about your research.

![]()

![]()

Originally from Wigan, John Wilson is a QC at 1, Hare Court, London who was called to the Bar in 1981. He has written or contributed to a number of academic text books, written very many articles and is a published poet.

Originally from Wigan, John Wilson is a QC at 1, Hare Court, London who was called to the Bar in 1981. He has written or contributed to a number of academic text books, written very many articles and is a published poet.

Wilson drew on his many years of experience of family law (and in the early days criminal law) and upon the misogyny and homophobia which were characteristic of the law at the time the novel is set.

When not working in London, Wilson spends as much of his time as possible in the South of France, where the novel was written, and travels extensively.

Discover more from Short Book and Scribes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.