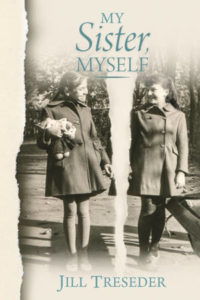

ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Extract from My Sister Myself by Jill Treseder @Jill_Treseder @SilverWoodBooks #RandomThingsTours

Today, I have a great extract from My Sister Myself by Jill Treseder to share with you today. I’m seeing some fantastic reviews for this book. My thanks to Anne Cater for the place on the tour.

![]()

Hungary, 1956. Russian tanks brutally crush the revolution against the Communist regime. Sisters Katalin and Marika escape Budapest with their family and settle in London.

However, the past is not so easily left behind. Their father is a wanted man, and the sisters’ relationship hangs in the balance. Their futures are shaped by loss. For Katalin, this means the failure of her ambition and a devastating discovery; for Marika, an equally heart-breaking experience.

Caught between their Hungarian heritage and their new lives in Britain, the sisters struggle to reconnect. Family secrets are exposed, jeopardising Katalin’s and Marika’s identities.

Can their relationship survive war, division and grief?

![]()

1

It’s another stifling day. All the windows in the apartment are open: Mama’s attempt to create a through-draught. But not a current of air moves. Katalin longs for their old house in Buda where there was nearly always a breeze, and a garden too. Here, in the middle of Pest, there is neither. The tall buildings trap and concentrate the heat like giant radiators.

‘We have a home,’ Papa would say when Mama complained. ‘We are all together.’

Katalin is bored. Mama has given in to Marika’s whining and is reading to her, so she goes in to the bedroom to practise.

She starts with some warm-up exercises holding on to the rail at the end of the bed, although it’s too high to work properly as a barre. Then she climbs up to step along the rail and across to the windowsill, turning and stepping back. There’s a rattle and screech of brakes from a lorry four floors below, but she takes no notice. It’s all about balance and control. She is going to be a ballerina. A dancer must practise every day. She is six years old. Along and across, turn and back, placing the soles of her feet carefully, trying only to look ahead, feeling the sweat trickling down her spine.

Her rhythm is spoilt when she notices Marika standing in the doorway. Watching. Bother. Walking on the bedrail is forbidden, especially when her little sister is about – which she nearly always is, being demanding and sticky.

‘I thought Mama was reading you that story.’

Marika makes a face. ‘Stupid book. I hate the princess.’

‘Just ‘cos she doesn’t look like you.’

‘I can do that.’ Marika climbs onto the bed and grips the bedpost.

‘No you can’t.’

‘Can, so.’

‘You’re not allowed.’ Katalin jumps lightly to the floor.

Marika’s legs aren’t long enough to climb onto the rail so she hangs on to it upside down, clinging by her hands and ankles.

Katalin can’t help giggling. ‘You look like a monkey.’

‘I’m a sloth, silly. Can’t you tell?’

Katalin shrugs and makes for the door. There’s a thud behind her.

‘Help with this.’ Marika is pulling at the washstand to drag it toward the bed. The legs judder on the boards.

‘Shush! Mama will hear. What are you doing?’

‘Getting on the rail.’

Katalin stands back, arms crossed. ‘You’ll never…’

‘I’ve done it before.’

‘Copycat.’ Katalin feels a feather of anxiety. What if Mama comes in?

Marika is on the marble top in a second, and from there onto the flat wooden rail. Agile but graceless. She wobbles as she treads along it.

‘Okay,’ Katalin says as she gets to the end. She’s about to say, ‘Okay you did it,’ and put a stop to the whole thing, but her sister isn’t finished. She is poised on the rail, eyeing the windowsill.

Her legs are too short. She’ll have to jump and how will she stop the momentum of her fat little body? Katalin pictures her roly-poly sister flying through the window. She might land on top of a tram. She might carry on flying, out over the rooftops and miles away.

These fantasies spin through her head in the second before she realises that Marika really could fall through the window. She herself is taller and would hit the top of the frame, so it couldn’t happen to her. And anyway, she has superior control. Unlike Marika.

‘I’ll tell. I’ll call Mama.’ That would put her at an advantage, and she might not get a hiding.

‘I’ll say I’m copying you. I’ll say you dared me. Anyway, shut up. You’re putting me off.’

No more Marika. Her stomach doesn’t know what to do with itself at the prospect. It’s griping, and jumping like the tadpoles in Grandmother Varga’s pond.

Seconds pass. She could grab the arm that is see-sawing above her head as Marika steadies herself. She could push her sister onto the bed. She could run and stand in front of the window and catch her.

She senses a gathering above her, a stillness. Marika takes a breath. Katalin is holding hers. The heaviness of the room presses hot on the top of her head. She tries to move. But Katalin is paralysed. She cannot move.

A whirlwind of noise shatters the silence, a tornado hurtling in from the door and across the room to land in a screaming heap against the wardrobe. The room goes spinning. Katalin buckles to the floor.

When she looks up, a yelling Marika is lying securely across Mama’s lap. Mama is glaring across at Katalin, her mouth slightly open, as if she might say something. She holds the stare and Katalin is frozen in that gaze. Then Mama gathers Marika and takes her off to the kitchen.

![]()

![]()

(from www.jilltresederwriter.com)

I started writing in a red shiny exercise book when I was seven years old. But in that time and place it was an ‘invalid’ activity, was overlooked, but never went away. It was many years before I felt able to call myself ‘writer’.

I started writing in a red shiny exercise book when I was seven years old. But in that time and place it was an ‘invalid’ activity, was overlooked, but never went away. It was many years before I felt able to call myself ‘writer’.

But there came a day when the phrase ‘I am a writer’ no longer sounded pretentious, but legitimate, and even necessary. Was it because I had a writing room instead of the corner of a landing? Or because I spent more time writing? Or because I’d got better at it? Or because I get miserable and bad-tempered if I don’t write? Probably a combination of all of the above.

Writing is my third career. The first was as a social worker with children and families, a job I loved, but left because I could no longer cope with the system.

This led to a freelance career as an independent management consultant, helping people to handle emotions in the work context. I worked in the IT industry, in companies large and small, as well as public organisations. Later I became involved in research projects concerned with the multi-disciplinary approach to social problems such as child abuse. So, in a sense, I had come full-circle.

All these experiences feed into the process of writing fiction, while my non-fiction book ‘The Wise Woman Within’ resulted indirectly from the consultancy work and my subsequent PhD thesis,‘Bridging Incommensurable Paradigms’, which is available from the School of Management at the University of Bath.

I live in Devon and visit Cornwall frequently and these land and seascapes are powerful influences which demand a presence in my writing.

Writers’ groups and workshops are a further invaluable source of inspiration and support and I attend various groups locally and sign up for creative courses in stunning locations whenever I can. I try doing writing practice at home but there is no substitute for the focus and discipline achieved among others in a group.

I have written some short stories and recently signed up for a short story writing course to explore this genre in more depth.

I live with my husband in South Devon and enjoy being involved in a lively local community.

Thanks so much for the blog tour support Nicola x