ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Interview with William Fagus, Author of The Purple-Bellied Parrot #RandomThingsTours

Welcome to my stop on the blog tour for The Purple-Bellied Parrot by William Fagus. I have an interview with the author to share with you today. My thanks to Anne Cater from Random Things Tours for the place on the tour.

![]()

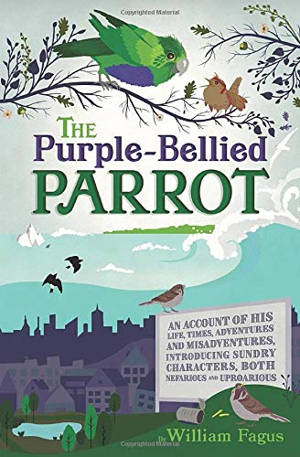

Discover … The power of the ‘HhhuuuUUTTT!’Ever feel you are living the wrong life? Ever feel another life, your should-be life, is out there waiting for you, if only you had the courage to …Do you like tinned pineapple chunks? Have you answered yes to any of those questions? Then follow the Purple-Bellied Parrot on a rip-roaring, globe-spanning adventure packed with unforgettable characters. His quest to live his should-be life.It Begins: In the sterile apartment of a city executive with unruly nasal hair where the Purple-Bellied Parrot cannot even do the very thing he was born to do. It Ends: On the shores of a distant land after an epic journey which tests his courage, his ingenuity and the bonds of friendship — to the limit.The Purple-Bellied Parrot is a spell-binding, life-affirming tale, with the power to evoke laughter and tears from readers 11-100 years old. (Parental Note: contains occasional mild imprecations.)

An Interview with William Fagus

Tell us a little about your background.

I was born in Stoke on Trent in a working-class family.

I left school aged 16, and confronted the world of work armed with three middling GCSEs. My parents just wanted me to ‘earn my keep’, so a career or further education were positively discouraged.

Until the age of 40, I did mainly manual work: builder’s labourer, sawyer, carpenter, window cleaner.

In my forties I went to university, where it turned out I had a talent for writing academic essays. I got a 1st at BA and a Distinction at MA.

I finished up with a PhD in architectural history.

My interests: I like walking in wild open spaces, historic buildings (not posh ones), ornithology, traditional carpentry skills; I play blues guitar in the manner of BB King (his 50s and early 60s stuff).

Where did the original idea for the Purple-Bellied Parrot come from?

I began writing it so long ago it is hard to remember. I remember, though, being attracted by the name, the Purple-Bellied Parrot, a species that lives exclusively in discrete areas of south-east Brazil. I thought what a wonderfully alliterative name it was and how it might make a good title for a children’s book. During a somewhat stop-start writing process, however, the novel changed and became more sophisticated, and I realized I was writing something other than children’s literature (although there is much for children to enjoy).

I should add that most authorities now call the species, rather humourlessly I think, the Blue-Bellied Parrot.

You say the writing process was stop-start. Why, and what made you finish the book?

I started writing it while I was looking for work following my PhD. I was discovering that a PhD seemed to be an impediment to getting a job! Then I took a couple of short-term opportunities, and so the book was put on hold. I finally found a permanent job with a government advisory body which I thought would use my expertise and skills. It turned out to be the most boring and unfulfilling job I’d ever done — and I’ve done some boring and unfulfilling jobs in my life! I’d been there for a couple of years and thought, I’ve got to get out of this or I will go mad. I know, writing a popular book might be the answer. So, for the twelve months from late 2017, all my spare time and creative energy went into finishing the book.

The plot contains lots of twists and turns and spans the globe. How did you develop the story?

I’ve been a bird watcher all my adult life. (Please don’t call me a twitcher!) I knew a little about the illegal wild-bird trade. But all I had in my brain when I started was the bird, the flat where the pink-faced man lived, and that somehow the bird would try to get home. I seem to be different from other writers. I don’t use story boards or wallcharts or shufflable ideas cards or anything like that — the occasional post-it note stuck to the monitor is as far as I go. I just sit down, sometimes with ideas and sometimes not, and start writing.

My best ideas come to me when I’m actually writing, and I have to make a note at the end of the page quickly before I forget. Sometimes an idea for a scene many pages ahead will pop into my mind — that happened with the scene in the African market — and I just have to break off and rough it out. Normally I keep a document open called ‘Ideas’ or similar that I can get at straight away. Ideas often come to me in the morning darkness when I’m awake (I’m a poor sleeper), or when I’m out for a walk — sometimes whole episodes or passages of dialogue. Sometimes it’s like I’m fit to burst, and I have to leap out of bed or rush home and get it down. It was the same when I was writing my thesis. Vague ideas would be floating about in my mind, and then they would begin to coalesce.

Your characters are memorable and extremely vivid. Shug, for example, is very strong. How did you come up with his character?

I enjoy creating characters more than any other facet of writing. I don’t want to give too much of the plot away, but I needed to solve a plotting problem and I remembered having read about an albatross in a similar predicament to the one Shug finds himself in, and I thought he would be an ideal solution. The name I filched from a character in a Scottish comedy series made in the 1990s called Rab C. Nesbit. One reader told me that he hated Shug. Result!

Why did you decide to put footnotes in the book?

Well I suppose it is a swipe at academic writing — much of which in my experience is of a deplorable standard. I’d be writing and I’d get all these ideas for jokes, or I’d find nuggets of information which didn’t fit in with the main flow, so I thought, why not use footnotes? They also lend the book a different, perhaps more authorial, voice — albeit eccentric. I thought at first they might distract from the story and during the final edit I agonized about taking them all out. But I’m glad I didn’t because people seem to love them.

Much of the book takes the form of a journey ‘The Trip’, and the reader experiences this from a birds-eye point of view. How did you manage to convey this so successfully?

A combination of imagination and research. I’ve never been to the Pyrenees, Extremadura, Tangier, Nouadhibou in Mauretania — let alone the St Peter and St Paul archipelago in the western Atlantic, so I traced their journey, south through western Europe and down the west coast of Africa via satellite imagery on google maps and streetview. I had my own bird’s-eye view of the landscape.

Tell us a little more about your writing process.

Well, I generally just sit down and start writing. I might have some concrete ideas in my head; I might not, but I’ll sit down and see what and who turns up. It’s a process of discovery for me — just like the reader.

What about writer’s block?

I am usually able to write something, and if I really get stuck, I’ll go out for a walk or saw a piece of wood or something. To anyone who has writer’s block I would just say to sit down and start writing — anything. Even unpunctuated stream of consciousness stuff is good. This is not to say I find writing easy. I have a lazy brain and sometimes I will do anything to put off the moment — hoover the crumbs out of the keyboard, wash the dishes, rinse out the recycling, play my guitar. Sometimes fear prevents me from beginning: the thought that I might have ‘lost it’, that I won’t be able to write anything any good. I start each session by editing the previous day’s work — it seems to warm up my brain. But, because I enjoy the editing process, this too can become procrastination.

Did you use a professional editor for The Purple-Bellied Parrot?

No. I know all the books tell you to because it is hard to see the flaws in your own work, but I didn’t. I think I am a good editor. When I was at university fellow students asked me to look at their work, and now friends often ask me to cast an eye over any important documents they are unsure of. I have edited a number of documents on a professional basis. The process with my own writing is: after that initial next-day edit I leave the text alone, to stew. I don’t look at it for as long as possible, a good fortnight at least. Then, when I return to edit, I can look at it with fresh eyes and see the errors and inept writing.

I should say that I did ask a friend to carry out the final proofread before I published. Because you have lived with the book for so long, it is impossible to spot every typo. It is like trying to spot mistakes in a painting when it is two inches from your nose. For the eagle-eyed there are still a couple of typos in The Purple-Bellied Parrot. In my defence, I recently read Farewell my Lovely by Raymond Chandler, a book re-published in many editions, and there were a couple of typos in that!

What do you mean by inept writing?

If you want to insult me simply tell me The Purple-Bellied Parrot is overwritten. I can’t stand overwriting (I’ve done it myself!). It might be long descriptions of people and places peripheral to the story; adverb cloggage; treating the reader like an idiot by leaving nothing to the imagination and telling us constantly how a character is feeling or writing every miniscule event in a scene. A mundane example, I recently read something like: ‘He parked the car and walked across the carpark, unlocked the door to his house, pushed it open and turned on the light.’ Start the scene in the house, please. We can work out the rest.

I see the writer’s job as transferring the thoughts in his/her brain into the reader’s brain via those squiggles on the page, and I want to do this as economically as possible. I start an editing session by asking myself, ‘Now, what can I cut out?’

Another bugbear is lazy writing. I recently read in an award-winning novel a character described without irony as having ‘chiselled’ features. Okay, we all have to resort to cliché sometimes, but come on, make an effort.

Something I believe 75% of the time: Writing is like a football referee. If it is doing its job well, you shouldn’t notice it.

Are you not over-emphasizing the importance of ‘good’ writing? What most readers want is a good story. If it’s a good story then they don’t notice or care if has too many adverbs or clichés or descriptions of the weather.

True, you can get away with a lot if the basic story is a cracker and its structure is ok. Many millionaire authors prove that, and I’m sure they would find my meagre bank balance hysterical.

Do you ever write in longhand?

Rarely. If I am away from a word processor I might scribble something down if I get a good idea. I once wrote out a whole scene from The Purple-Bellied Parrot like that, but it was a real pain in the rear end to type up.

Who are your favourite authors?

I don’t really have favourites. Truth be told, I don’t read enough novels, or rather finish enough novels. I’ve started four recently — all highly acclaimed — and only finished one. And I always give them a chance, around eighty pages or so.

There are writers whose craft I admire. I like Annie Proulx, especially The Shipping News and Close Range. There’s Steinbeck; Ian McEwan — his Atonement is one of only two books to make me cry. Who else? Elmore Leonard for his get-the-job-done economy; Kate Atkinson for her apparently effortless prose; Jerome K Jerome. Joseph O’Connor is a highly-skilled writer, but I don’t like all his novels. One of my favourite books is Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man, a masterclass in character creation, but overlong by a couple of chapters (I think most novels are too long!). Crikey! (as Chalkie a character in my book might say) I’ve just realized most of those are male. I’ve just started The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald, so I’ll see how I get on with that.

Influence for The Purple-Bellied Parrot, though, is more cinematic than literary. Think The Ladykillers (1955 version), Curse of the Were-Rabbit, Jaws (obviously), even Tom and Jerry. You’ll also spot references to the Rocky films, The Shawshank Redemption, Dambusters and even Full Metal Jacket.

Is there anything about The Purple-Bellied Parrot you are unhappy with?

Apart from a vague idea at the outset that it was going to be a children’s book — which it turned out not to be — I never had a target reader for The Purple-Bellied Parrot. My blurb says it is suitable for readers 11-100 years old, and it is. But in trying to be so scattergun all-inclusive, will I alienate readers? Is it too adult for younger readers and too young for adult readers? I worry about the title. Will teenagers want to read about what they think are simply the adventures of some parrot and, indeed, will some adults? Anyway, the toothpaste is out of the tube now.

William Fagus is a pseudonym.

![]()

![]()

The publicity-shy William Fagus lives in a remote location in an upturned fishing smack with a parrot and sundry antique musical instruments and carpentry tools.

The publicity-shy William Fagus lives in a remote location in an upturned fishing smack with a parrot and sundry antique musical instruments and carpentry tools.

The redoubtable Mrs Lush, his cleaning lady and confidant, is his most frequent visitor.

William Fagus’s biography, of uncertain origin and dubious veracity, is available here: http://www.williamfagus.com/fagus_biog.html

Thanks for the blog tour support x