ShortBookandScribes #BlogTour #Extract from Ring the Hill by Tom Cox @cox_tom @unbounders #RandomThingsTours #RingTheHill

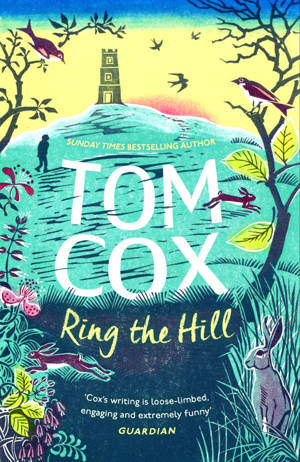

I’m delighted to share an extract from Ring the Hill by Tom Cox with you today. What a beautiful cover this book has and I’ve no doubt the content matches it. My thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours for the place on the tour.

![]()

A hill is not a mountain. You climb it for you, then you put it quietly inside you, in a cupboard marked ‘Quite A Lot Of Hills’ where it makes its infinitesimal mark on who you are.

Ring the Hill is a book written around, and about, hills: it includes a northern hill, a hill that never ends and the smallest hill in England. Each chapter takes a type of hill – whether it’s a knoll, cap, cliff, tor or even a mere bump – as a starting point for one of Tom’s characteristically unpredictable and wide-ranging explorations.

Tom’s lyrical, candid prose roams from an intimate relationship with a particular cove on the south coast, to meditations on his great-grandmother and a lesson on what goes into the mapping of hills themselves. Because a good walk in the hills is never just about the hills: you never know where it might lead.

![]()

JENNY DOESN’T LIVE HERE

(2014–19)

The lunar eclipse had just happened and people in town were saying it had been having a dramatic effect on everyone’s sleep, infiltrating dreams in troubling, vivid ways. Always a bit out of step with town, I’d slept soundly during the eclipse and got my weird dreams out of the way a week earlier. In one dream, my washing machine, which already displayed a tendency towards nomadism, totally broke free of my house to start a new life on the road, performing for coins. In perhaps the most disturbing dream, I dream-woke on my back, floating in deep water, having made the error of falling asleep in the sea. I sort of assumed in the dream that I was somewhere a few hundred yards off the shore of the hard-to-get-to Devon cove where I had done most of my recent swimming, but in truth there was no landmark to suggest I was actually near that cove, apart from the sea, which, while undoubtedly a very distinctive landmark, is a landmark only specific enough to tell you that you are somewhere on 70 per cent of the planet’s surface. I did get a sense that it was the particular kind of sea you get near that cove, but I couldn’t be sure. I woke up again, and realised that this was a proper waking and that I was in my bed and hadn’t really woken up in the sea at all.

It probably makes sense that I’d dream such a dream – a dream combining freedom, homeliness, comfort and danger – about my favourite Devon cove. I had been going to the cove regularly for over four years and developed a relationship with it that had, at times, bordered on addiction. Through the cove, I could to an extent tell the recent story of my life: the books I had read, the books I had failed to read, the changes to my body, the little shifts in life philosophy. I had fallen in love at first sight twice on the cove – quite a high ratio when you compare it to the same period inland, where I had only fallen in love at first sight once. In my garden there are a small selection of stones from the cove, including a chunk of smoothed tarmac, which looks like a conglomerate puddingstone but on closer inspection is almost certainly a former part of the road a couple of miles away beside Slapton Ley, which was violently ripped apart by Storm Emma in early 2018, in an astonishing reminder of the brute force of nature the likes of which you don’t see often in the UK. I have been physically attacked at the cove on fifteen occasions that I can pinpoint: fourteen of them by jellyfish, and once by a black Labrador, which swam over to me and climbed on my back, leaving my ribs covered in scratches. I doubt any of these attacks can be considered malicious: the jellyfish were just defending space that is rightfully more theirs than mine, and I think the Labrador – which was owned by a semi-oblivious Dutch man – just wanted a nice, big, wet cuddle. At least the salt water quickly went to work on my injuries, as it has done on pretty much every injury I have had upon my arrival at the beach, magically curing small patches of eczema, cuts and bites.

Down at the far end of the cove is a small, unofficial nudist section. I could probably join its ranks, as I feel increasingly relaxed about the idea of being naked in public and in the water, but something stops me – maybe it’s the memory of those jellyfish stings. The nudists are nearly all 65-plus and uniformly almond-brown. Clothed people arrive, have barbecues, throw balls for dogs, get in the water and yelp about the cold, then leave, but the nudists abide: sleeping a bit, swimming a bit, sleeping some more. I have seen no evidence that they ever leave the cove. I would not be surprised at all to venture into the caves beneath the cliffs and find the hobs where they cook their fresh mackerel breakfasts, the beds where they sleep and have surprisingly agile pensioner sex, and the showers where they scrub the pebbles and salt off their wiry old bodies. Maybe people who have visited the cove a few times think not dissimilar thoughts about me. ‘That hippie with all the dog scratches on his chest is here again,’ they might say. ‘I wonder which subterranean part of these cliffs is his home.’

I don’t think the cove is the best cove in Devon and Cornwall for swimming – there are warmer coves, with clearer, more benevolent water and better rocks to leap from – but in an equation which weighs up ease-of-swim and proximity to the two houses in Devon where I’ve lived, it has worked out as the logical choice. I have grown to trust the cove, without in any way making the mistake of taking it for granted. While swimming there, I often starfish out and let myself float. It’s my sea-swimming equivalent of the time you might take for a breather between lengths at a pool, and doubles as a version of meditation for someone who always intends to meditate but rarely does. I am very relaxed when I’m in this state, my mind a fuzzy blank, preoccupied only by the tiny noises beneath the surface, which, like everything at the cove, are always subtly changing. I doubt I could fall asleep in this state, I am not complacent enough to fully give myself over to a state in which I could – unlike in my dream. This lack of complacency might be a result of the period during my childhood when my dad would regularly convince himself that my mum was going to fall asleep in the bath. ‘TOM, ARE YOU UPSTAIRS?’ my dad would ask. ‘Yeah,’ I would reply. ‘CAN YOU CHECK YOUR MUM HASN’T FALLEN ASLEEP IN THE BATH?’ Following which I would knock on the bathroom door and ask my mum if she had fallen asleep in the bath and my mum would confirm that she had not fallen asleep in the bath.

If, like me, you are really enjoying this extract then you can go on to read the whole of this chapter by clicking here.

![]()

![]()

Tom Cox lives in Norfolk. He is the author of the Sunday Times bestselling The Good, The Bad and The Furry and the William Hill Sports Book longlisted Bring Me the Head of Sergio Garcia. 21st-Century Yokel was longlisted for the Wainwright Prize, and the titular story of Help the Witch won a Shirley Jackson Award.

Tom Cox lives in Norfolk. He is the author of the Sunday Times bestselling The Good, The Bad and The Furry and the William Hill Sports Book longlisted Bring Me the Head of Sergio Garcia. 21st-Century Yokel was longlisted for the Wainwright Prize, and the titular story of Help the Witch won a Shirley Jackson Award.

Thanks for the blog tour support Nicola x